The Road to Self-Sufficiency

A TechnoServe staffer writes about her experience at a TechnoServe training workshop for cotton farmers in Swaziland.

I love winding, open roads that disappear into the horizon. That point in the distance where the road and sky meet always beckons to me, tantalizing me with a world of possibilities, new experiences and a freedom far removed from anything in my day-to-day life.

I found myself on such a road in the lowlands of Swaziland earlier this year. In the company of Swazi colleagues, I cruised along a curvy stretch hugged by rolling hills and a vast blue sky. I took in the unfamiliar sights — women gliding along the side of the road with enormous baskets perched on their heads, carrying their load with a calm and resilience that I envied; small clusters of homes and communities nestled amidst the majestic, imposing presence of the hills; and farm plots of varying sizes, adding texture and diversity to the landscape. I learned from my colleagues that most Swazi farmers plant corn as one of their primary crops. And yet, because of the dry, hot climate of the lowlands, the corn crop almost always succumbs to the heat and lack of water, and farmers lose a primary staple on a regular basis.

Hence, our presence on this beautiful, winding road.

We turned onto a nearly invisible dirt path off the main road and headed to a dusty, barnlike building, where we prepared to present a training workshop to cotton farmers participating in the Swaziland Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Program (SWEEP) program, funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development. The program supports economic growth and job creation by establishing and expanding small or medium sized enterprises (SMEs), including smallholder farmers, in Swaziland. Because of the fickle nature of corn in this part of the country, TechnoServe’s advisers worked with select farmers to plant cotton instead, as the soil and climate created an environment much more conducive to cotton than corn. Still, because of a deeply ingrained reliance on and attachment to the staple, and despite many failed harvests, farmers strongly resisted switching over to cotton. The ones who chose to plant cotton do so alongside their corn plots.

Parking our vehicle in the open field, we approached the barn where several farmers had already begun to set up the empty room with long, flat benches. Until that moment I had known this project only on paper, as a set of numbers and program goals to be met. Now that story came to life as I looked into the proud, regal faces of these farmers ambling in, one by one. Settling themselves comfortably on the benches, men on one side, women on the other, the soft chatter slowly quieted when one woman stood up and faced the group, initiating the call and response greeting. Then, closing her eyes, pausing to absorb the reverent hush blanketing the room, a beautiful Swati melody sprang from her mouth, joining with the voices of the other participants in a simple song whose rich harmony hummed through my veins and raised the hairs on my skin.

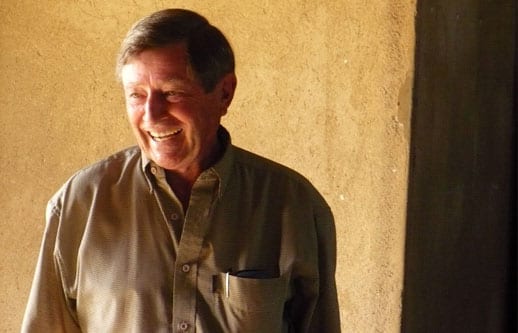

With the last notes fading into silence, the farmers turned their attention to the presenter, Mike Burgess, an expert trainer who shares his technical expertise to farmers in SWEEP’s cotton and livesmtock programs. Throughout the two-hour presentation, they listened intently, asked questions about technique, made comments and shared lessons learned from their own experiences. They talked about what TechnoServe’s assistance meant to them — how, for example, learning the correct way to apply herbicides increased their average cotton yield from three bales to five per day. On this particular training day they observed and practiced cotton picking techniques, and discovered how small changes in their current picking methods could make a big difference in efficiency and quality, and ultimately, revenue and income.

After the session ended, the farmers milled around over lunch, discussing cotton grade and quality with the presenters and among themselves. I couldn’t understand the Swati conversations, but I felt a palpable energy and enthusiasm as they filed out of the barn and made their way back to their homesteads. As lead farmers, these participants would transfer the knowledge gained in this session to the other cotton farmers in their teams, building the community’s capacity to overcome corn crop shortages and failures.

Back on the road again, my Swazi colleagues and I shared our excitement over the success of the workshop. They marveled at how much the farmers’ level of interest and engagement had increased from the beginning of the project to present day, as evidenced by the workshop’s success. There still remained a great deal of work to do and a host of challenges to face, but at least for now we could all look down the road with hope.

Yuniya Khan formerly provided support in TechnoServe's Program Development unit.